In most European countries many actors, governmental (national, regional, and local authorities) and non-governmental organisations, are involved in organising and managing housing facilities, as well as providing accommodation for asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants.

However, the reality is that for many asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants, the resources provided by the government, municipalities, or local organisations are not accessible. This leads to a serious lack of adequate housing which has become one of the major obstacles to really being part of the city.

In addition, depending on their legal status, gender, and nationality, these particular groups face manifold barriers, especially financial and social disadvantages to acquiring decent housing. For many, housing is scarce, rents are high, living conditions are poor, and often the only neighborhoods available are deprived areas. Insufficient and inadequate social assistance often leads vulnerable groups amongst the immigrants, such as new arrivals, undocumented migrants, asylum seekers and refugees, to situations of homelessness.

This leads to situations of extorsion and unhealthy living conditions, which in return has a massive impact on their health, possibilities to build a life and dignify their existence. In many cities, it is required to have an official address in order to access resources provided by the municipality. By not being able to find a stable and legal home, their already limited access to resources gets limited even further.

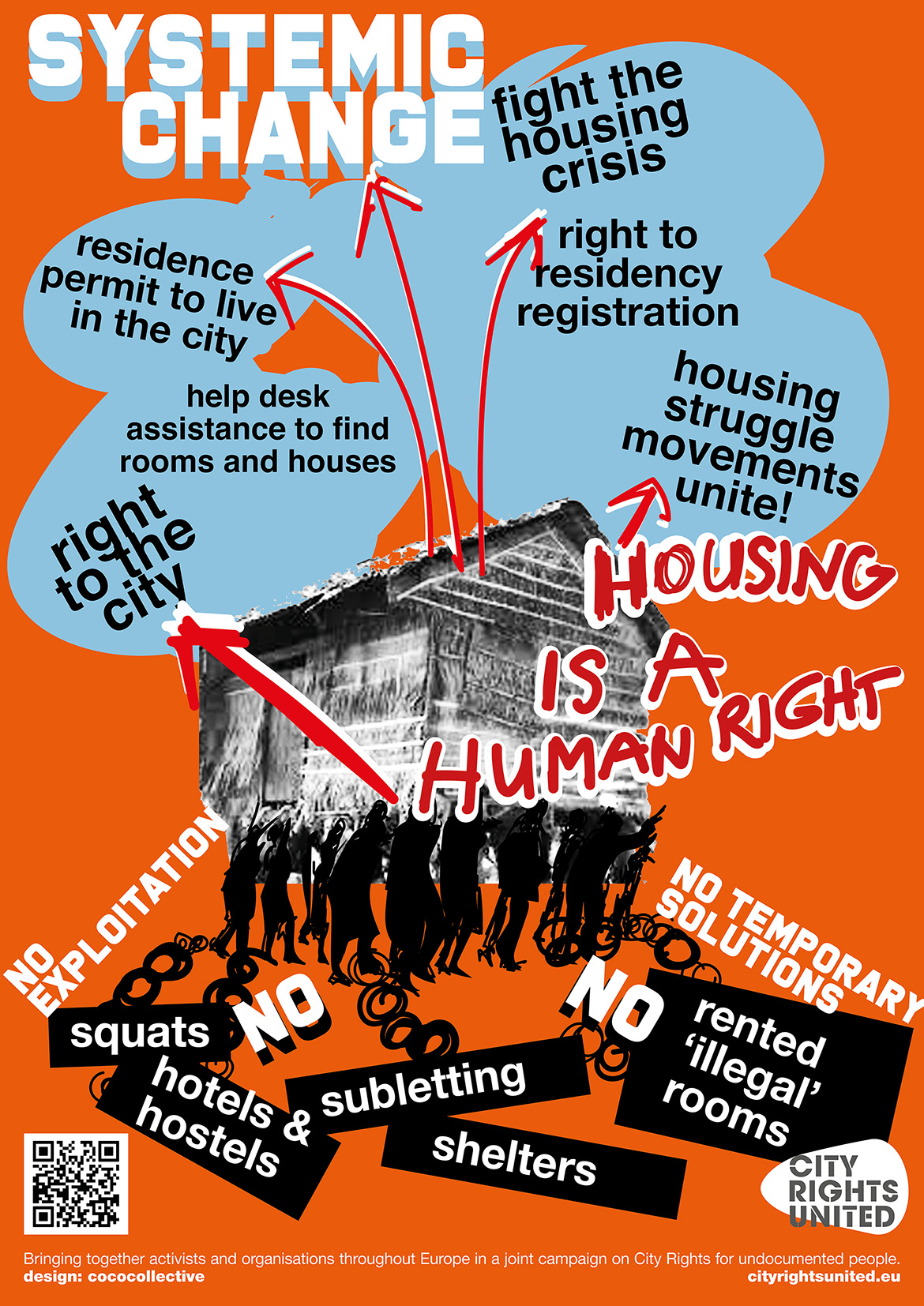

Housing is a pressing topic for each organisation supporting refugees, people of color, migrants, undocumented people in their cities. During the meetings of City Rights United, we exchanged strategies and systems to organise housing for undocumented people, only to discover that perhaps the bureaucracy differs, the struggles and solutions are more or less the same. All solutions discussed are so-called ‘band-aid’ solutions, temporary solutions used in emergency situations like squatting, illegal rent or municipality shelters.

In order to really make a systematic change, in order to really fight the housing crises in many large European cities, we need coalitions, solidarity, organisation and movement. We need to connect the voices of undocumented people and refugees to the already existing movements organising for systematic solutions to the housing crises in their cities. We need to get those movements to show solidarity and together as a coalition fight the trend where houses are for profit and not living! We need a new political approach on public housing and on the -right to housing as a human right -at a national and local level- can intervene within a phenomenon of this size.

Napels

The housing emergency in Italy has become a structural issue that perfectly reflects a 30-year crisis within government decisions on the right to housing. The subaltern classes are the first to pay the consequences, given that they are most exposed to the phenomena that cause poverty and social marginalization, especially during the pandemic and ongoing economic crisis. According to recent census data, 2,000 people are homeless in the city of Naples alone. Nonetheless, the city’s public dormitory has only 400 beds available. The issue of temporary and more stable housing availability (through housing contracts) creates an ulterior problem with the system because residency certificates are essential to accessing the social infrastructure (opening a bank account, receiving government subsidies, etc.). Citizens of foreign origin or asylum seekers, especially those who have exited government hospitality mechanisms, are most exposed. Other than the difficulty of finding landlords who will offer them legally leased housing (with a housing contract), they are often subject to racism from landlords who refuse to rent their properties to non-European citizens. Their official residence is connected to the release and renewal of the “permesso di soggiorno” residency permit. This growing need has created a stratified black market for the sale of residency certificates, often managed by criminal organizations, Neapolitan and foreign intermediaries, and corrupt municipal employees.

To combat this phenomenon of blackmail and abuse, we have created a designated help desk for the right to residence within the Ex’OPG Je So’ Pazzo. Through our ongoing strategic struggle, as a political instrument, we created a channel to negotiate with the municipality, forcing them to consider our association as an accredited institution capable of requesting virtual residence for subjects that are supported by our legal team. This service (providing accredited virtual residence) is primarily requested by Italians without stable housing and asylum seekers that live outside of hospitality centers, who have enormous economic difficulties and are at risk of losing their residency permit. Part of our work involves orientation towards searching for stable housing and providing information on residents’ rights. In 2018 we occupied the abandoned church Sant Antonio a Tarsia, where we are carrying out a small project of self-guided hospitality for people with housing emergencies. The process is only suited for 7-8 people each year, who are either documented or undocumented, and each person co-creates a social rehabilitation project tailored to their needs. The dimension of this emergency has given us a valuable data point: organizing can help intervene within the emergency and can help a small number of people, but only a new political approach on public housing and on the -right to housing as a human right -at a national and local level- can intervene within a phenomenon of this size.

Amsterdam:

Since 2012 We Are Here, the refugee collective based in Amsterdam, has been campaigning against the inhuman Dutch asylum policy. WAH squatted, in cooperation with the squatting movement, many houses to show the inhumane situation in which they live and to ask for attention for the situation of refugees whose asylum requests have been denied but who can’t be deported. Time and time again We Are Here has been evicted, putting them out on the streets and back into uncertainty again. New shelter places and programs are opened: but they only offer a temporary solution as well.

Other undocumented migrants live scattered throughout the city, arranging their own housing and a significant number are exploited by malicious intermediaries. They rent without a tenancy agreement and without knowing the owner of the property. The rent they pay varies but is sometimes between up to €2500 per month for a small space. Those who cannot find a place to stay on their own are in principle vulnerable because an undocumented homeless person can’t make use of the regular municipal services.

These refugees and undocumented people are not the only people in Amsterdam looking for shelter: many Amsterdam-based or born people are unable to find a place to live as well. Homelessness numbers are rising and rising, eve doubled over the last 10 years. Social housing, which is the only affordable option for low to middle-income people, is being torn apart as real estate is sold to parties eager to capitalize on gentrification. Meanwhile, the waiting list for ‘social houses’ continues to grow for those who have been in need of housing for a long time. A new housing movement has started in 2021 in Amsterdam (called Woonprotest) to bring attention the systematic problems of the current housing crisis in the Netherlands. Amsterdam City Rights and PrintRights joined the protests to show how this crisis is influencing the most marginalized and vulnerable groups of the city. Now it is time to unite and demand systemic change instead of the band-aid solutions!