The LGBTQI+ working group is constituted by volunteers who have decided to come together to raise awareness on the situation of queer undocumented migrants.

During the last couple of months, the group has drafted a booklet in which we examined the legal definition of a queer refugee under the 1951 Convention and International law, the discrepancies among European states when it comes to the process of asylum, the importance of providing proof, and a general overview of the Dutch situation.

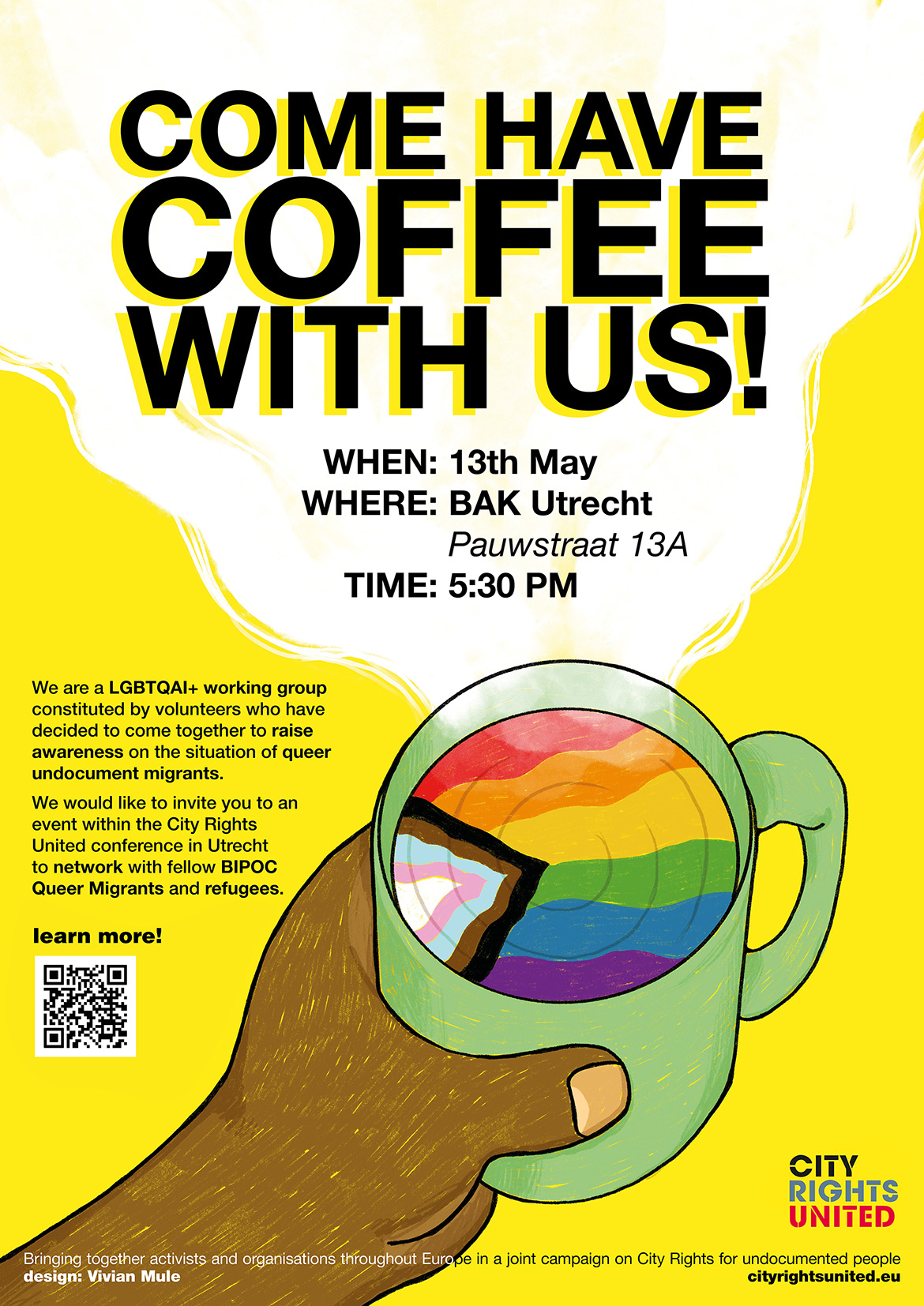

Collecting the information of this booklet has been a process mostly organised online. Only in February 2022 the group was able to meet in Naples at Ex OPG to discuss the needs of LGBTQI+ migrants. From these meetings the idea came up to start with organising a ‘safe space’ for LGBTQI+ refugee communities to come together and be together in a space that benefits them. During the City Rights United conference the first of such meetings is organised during which further steps will be discussed.

The Booklet is uploaded here on the website.

You can also find a summary and translation here.

DEFINITION OF REFUGEE

The Convention of 1951 relating to the Status of Refugees states that a refugee is a person having a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

LGBT+/Queer people fall under which of the aforementionned reasons?

It is notable that the Sexual Orientataion & Gender Identity (SOGI) ground has never been identified as an individual ground within the international community. One of the reasons might be the reluctance of some countries when it comes to recognize LGTB rights. Also, there is a tendency in finding difficulties to define the definition of “social group” since it is not defined in the aforementioned Refugee Convention.

This is the beginning of the struggle for the LGBTQI+ refugees. Further exploration in for example European Law highlight these problems again. They are therefore categorised as being a particular social group.

Along with the idea that queer refugees are members of a particular social group, -as it has been previously mentioned-, the Refugee definition stablishes that because of that reason “a well founded fear of been persecuted” exists. In other words, queer refugees need to prove that they fear for they security and stability in their countries of origin because they are queer. They need to convince asylum decision-makers by providing evidence of their claim. The level of the standard of proof, according to both, UNHCR and EASO (European Asylum Support Office) is a “reasonable one” meaning that the standar is a low one and the benefit of the doubt is given to the claimant. However in practice, authorities often apply a higher standard thus hindering access to international protection.

The local situation of the country of origin can often be explained and proofed using reports by official institutions, like NGO’s. Indeed, as it was mentioned before, the social group ground contains two aspects of one person’s life: self-identification and society´s perceptions as SOGI being a distinct social group.

Concerning the personal story, the focus is generally placed on the coherence and the consistency along with substantial proof such as personal photographs and/or videos, local/national media reports, participation in LGBTQ+ associations, etc.

The difficulty heare lies around the personal character of the questions that need answering. the fact that LGBTI asylum seekers originating from countries, in which persecution and/or discrimination of LGBTI people are highly prevalent, are often incapable of speaking about their sexual orientation, gender identity or their being intersex right away, for instance due to distrust or fear.

Perhaps one of the problematic issues concerning SOGI asylum claims, credibility presents itself as an enhanced obstacle even higher than other asylum claims. The difficulty relies sometimes in the fact that most claims remain undocumented and also the fact that one has to prove a very intimate aspecto of life (external and internal credibility). Stereotypes (specially western stereotypes and visions) are commonly present when processing asylum claims and also during the whole asylum process (stays in reception centers, dealing with stress, trauma, language barriers, etc).

These stereotypes tend to take the form of expectations according to Western countries: such as the existence of “coming out stories” (out and proud), involvement with LGBTIQ+ activism, attendance at LGBTIQIA+ social and nightlife spaces, familiarity and actively meeting the criteria expected with LGBTIQIA+ culture and the media, being sexually active according to the self-identified SOGI, and not ever having had heterosexual partners or children.

Proper training in LGBTQIA+ and diversity issues is thus extremely important for those working with such asylum cases.

In order to obtain the status of refugee, several interviews will be held for the immigration authorities to study each case. Interviews are CRUCIAL since, based on the information given, the status will be granted or denied.

In conclusion, queer refugees need to prove to immigration authorities and judiciaries that they are queer, that they fear persecution on the grounds of their sexuality, and that such fear is well-founded. The outcome of the claims is largely dependent on the existence of usually non-existent evidence. By implication, queer quests for refuge are regarded as easily made and impossible to prove.

Indeed, this is one of the most difficult grounds to comply with from a multilevel legal perspective: Geneva Convention, EU asylum system and EU member states national legislations. There is no doubt about the complexity of the LGBTQIA+ related issues and persons who make part of it. The latter is important to highlight given the fact that in this specific ground the application for international protection has to prove very intrinsec and personal aspects of one’s own life. Nevertheless, national authorities have the duty to not only process this kind of application but also set out adequate and fair treatment taking into account the different needs and diversity of the LGBTQIA+ population . The same applies for local authorities. private associations and institutions involved within the process. Let’s take action, create networks and defend our rights!